Ph

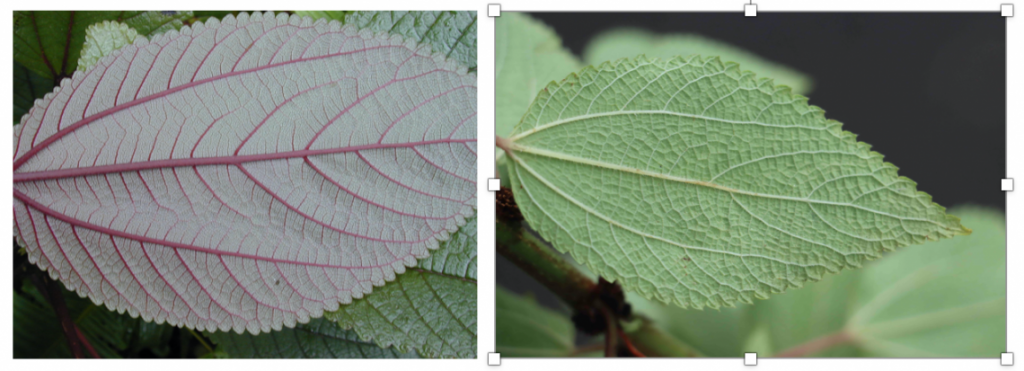

You may have noticed strawberry guava in your area developing strange looking lumps on the leaves. Those lumps are called galls. These galls are not caused by any disease or any nutrient deficiency, but are actually the homes of tiny insects that live inside the tissues of the leaves.

There are many types of insects that cause galls, but each insect species is attached to a specific group of plants – sometimes just a single species of plant. The insect and the plant developed a relationship over millions of years, allowing them to recognize each other. The insect uses a chemical signal to induce its host plant to use its energy to form a gall around the insect, which creates a home for the bug.

The action of creating a gall saps energy from the plant that the plant cannot then use on other aspects of growth, but generally most galls are not harmful to their hosts.

The strawberry guava gall-maker, Tectococcus ovatus, is a tiny scale insect. The female burrows into the leaf, preferably fresh new flush, and the plant forms the gall to make her home where she will lay her eggs. She will remain in that spot for the rest of her life. Her newly hatched young will eventually emerge and do the same, crawling to a new spot normally not very far from where they just hatched. These particular gall insects don’t fly, but are sometimes carried on the wind. Because of this, Tectococcus moves from plant to plant somewhat slowly. In order for them to travel long distances, they need the help of people.

Where did Tectococcus come from?

Tectococcus is a native of Brazil, just like its host plant, strawberry guava (Psidium cattleianum). It was introduced to Hawai’i in 2011 after a lengthy research project by entomologists and ecologists from the US Forest Service. For more than 20 years, Tectococcus was tested – first in its native country, then in quarantine in Hawai’i – to make sure it could not attack any important plants here. In no-choice tests, where the insect was given only one type of plant to live, Tectococcus was never able to survive – not even on its most closely related cousin, Psidium guajava (common guava). This was good news, because it meant that it could be safely released into the Hawaiian environment.

Strawberry guava is a notorious invasive weed in Hawai’i and around the world. It is classified as one of the World’s 100 Worst Invasive Species by the IUCN. It creates monotypic stands that don’t allow the growth of other plants, and the bright fruits are consumed by animals that spread the seeds for miles, allowing it to flourish deep in native forests and watersheds. In Hawai’i, strawberry guava forests are known to increase erosion and decrease water recharge, degrading ecosystem function and reducing habitat for native animals. It is also known worldwide as an agricultural pest, as the fruits are host for the fruit flies that restrict our farmers’ ability to ship fruits to the mainland. In 2023, the USFS Forest Inventory Analysis published a disturbing finding from Hawai’i: for the first time, an invasive tree had surpassed ʻōhi’a as dominant in number. Strawberry guava has begun outpacing ʻōhi’a in our forests.

How it helps

Even with heavy infestation, it is unlikely that Tectococcus will kill a mature strawberry guava tree. In Brazil, where Tectococcus and strawberry guava are found together throughout the forest, plants generally grow to around 12-15′ feet, and form a drooping canopy – completely unlike the 40 foot tall “prison bar” growth we see in Hawai’i! This is because strawberry guava without Tectococcus has none of the natural devices to keep it in check here like it does at home. The hope of ecologists battling to save native species is that reuniting the plant with its insect will slow it down, and give ohi’a (which has its own galls) and other natives a fighting chance.

For more information on SG biocontrol and applying Tectococcus ovatus.

Beyond Tectococcus: Other Gall Insects in Hawai’i

A gall insect evolved in relationship with one type of plant cannot just make a gall on another type; for example, the mite that cause hibiscus galls will not be able to talk to a mango leaf. They don’t speak the language! Usually plants find a way to balance the galls, and live just fine even with their little “moochers”.

However, sometimes a gall insect may arrive in Hawai’i that evolved with a close relative of a Hawaiian plant, and those can be potentially very damaging (see the case of wiliwili, below). If gall infestations on any plant become too heavy, they can change the structure of the leaves so much that the plant can lose the ability to capture water and light effectively. The level of damage galls can cause is dependent on many factors, including the overall health of the plant.

If you take a close look at the various galls on different plants, you may notice that they are different in shape, size and color. Each gall/plant relationship is unique. Below are some of the most commonly found galls in our environment.

ʻŌhiʻa Psyllids

There are a few psyllid species that are native and co-evolved with ʻōhiʻa. They do not cause significant harm to the plant – ʻōhi’a grow old and healthy even with galls on their leaves.

Hibiscus

Erineum mites (Aceria hibisci) can be found on different varieties of hibiscus plants. They suck nutrients out of the leaves and stems and release a chemical to induce the galls. If a plant becomes too heavily infested, the mites can drain so much energy they cause flowers to drop or never develop. Long-lasting infestations can leave the plant more susceptible to disease. Care should be taken to manage hibiscus galls to ensure they remain at low levels.

Wiliwili

The erythrina gall wasp (Quadrastichus erythrinae) arrived in Hawai’i in the early 2000s and began attacking trees in the Erythrina genus (coral trees), including the native wiliwili. The wasp lays its eggs in the leaf and stem tissue of the wiliwili, causing large galls on the plant. Because our native species did not co-evolve with the wasp, it had little defense, and was too susceptible. Heavy infestations were driving the tree to near extinction. But luckily, a biocontrol was released to help control the erythrina gall wasp.

There are many other galls that appear on plants in the Hawaiian environment. Found a strange gall on your plant? Send us a picture or bring us a sample, and we’ll work to get an identification for you!