A critical part of the work we do at BIISC is looking for new, potentially damaging, arrivals, In late 2017, BIISC botanists collected a mystery plant on a trailside early detection survey on the Kona side near the Makaula-O‛oma State Forest Reserve. It was at first easy to overlook, with no eye-catching characteristics to make it stand out from the lush greenery around it. However, trail users had reported its aggressive tendency, and its persistence even after they tried to control it. The BIISC team realized that this plant did not match any known introduced or native species on the island, and observed that it was reproducing naturally – and quickly – throughout the area: an alarm bell indicating a potential invasive species.

However, before declaring a new species invasive, careful investigation must be done – and the first step is ensuring a definitive identification of the organism. But this seemingly simple question became more vexing as the team pored over botany records: just what WAS this plant? With hundreds of thousands of plants in the world, many with little published information available, plant ID is not an easy task. The team reached out to plant experts on the island and across the state, but no one recognized this one. Samples and photos made their way to various botanists until in 2020 a Smithsonian botanist, working with colleagues from Europe, was able to pronounce that a little-known, low-profile shrub from Central America, Phenax hirtus, had somehow arrived in Hawai‛i.

Phenax taking over the understory

Phenax leaves and growth pattern

Hogging Space

Like another recent invader, the Queensland Longhorn Beetle, Phenax hirtus wasn’t known to be a pest anywhere else in the world before it appeared on the Big Island. It is unknown how either arrived here, but most likely it was a “keiki form” (larvae in the case of the beetle, seed for the plant) as an accidental stowaway, quietly arriving in some kind of soil, plant material, or packing crate. These sleeper species will often quietly proliferate and spread, unnoticed until they begin to cause a problem. This can make it difficult to enact a successful eradication plan; without previous research, we don’t always know how to control the pest. Information about the species’ life cycle, reproductive strategies, seed viability, climate tolerance limits – all can be critical to making sure control efforts are effective.

Phenax hirtus has many of the classic characteristics associated with invasive plants: it is shade-tolerant and can grow in undisturbed vegetation, including under a native forest canopy. It has a climbing nature, able to pull itself up over other vegetation to seek light and space. It even finds a way to grow amongst aggressive Himalayan (kāhili) ginger – a known “space hog”! Seeds are tiny and can spread easily on wind or water.

Phenax hirtus overtaking residential landscaping. (Photo: JB Friday)

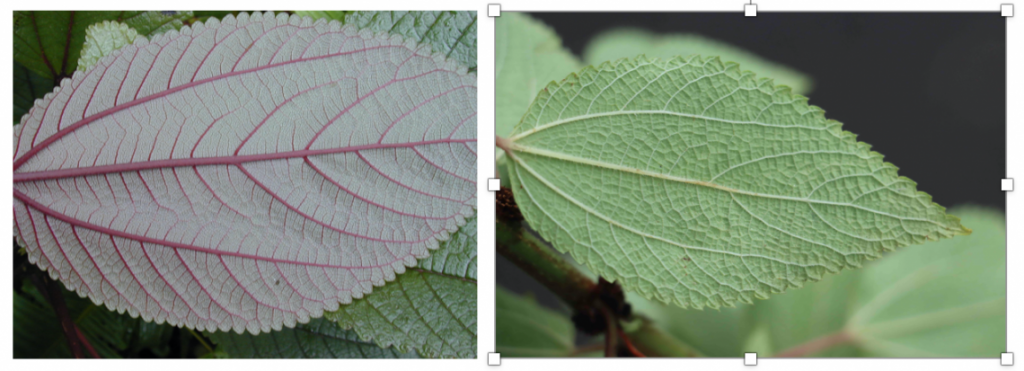

BIISC crews are working now to control outlier populations of Phenax in the Kaloko Mauka community where it was found and limit it from continuing to spread. Big Island residents are also being asked to be vigilant and take pictures of any suspect plants in other areas of the island. It is a nettle, the same large family as the native māmaki, so the leaves are similar, but generally skinnier and more green (not so much of the reddish veins that are generally present in māmaki). The best way to tell them apart: māmaki produces seeds in a distinctive fleshy white fruit at the end of the leaf node, while Phenax will have a dry brown ball of seeds.

Mamaki fruits (left) are fleshy and white, while Phenax fruits (right) are dry and brown. (Forest & Kim Starr; JB Friday).

In today’s world, some invasive pests are nearly household names in dozens of countries: Asian longhorn beetle, spotted lanternfly, red imported fire ants, giant hogweed. These pests make headlines the minute they appear in a new area. But Hawai’i, while at risk of these notorious invaders, is also uniquely vulnerable to taking a bad turn to invasive behavior. Life in Hawai’i evolved in isolation over millions of years, with a barrier of 2500 miles of open ocean dissuading colonization by new life forms. Biologists estimate that before human contact, a new species established in Hawai’i only about once every 10,000 years. Without the fierce biological competition and predation found on an African savannah or South American rainforest, our native species evolved without many of the defenses and protections that their continental counterparts had long developed.

The year-round temperate weather, novel native ecosystems with open niches, and multiple climate zones of the islands all provide opportunities for introduced species to become problematic in Hawai’i. With more introduced species reaching our shores today than ever before, it is critical to be vigilant and keep an eye out for anything new that appears unexpectedly, potentially posing a problem.

Mamaki leaves (left) tend to be more oval with reddish petioles while Phenax leaves (right) tend to be more narrow and green throughout. Photos: Forest & Kim Starr; JB Friday