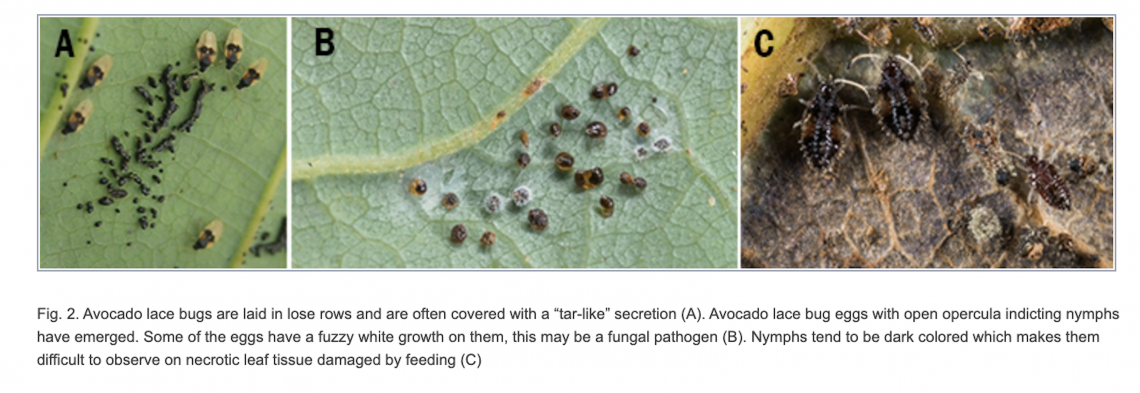

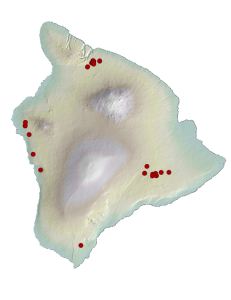

In August 2019, a resident from Puna submitted logs to the state Department of Agriculture office in Hilo. Those logs were the remains of a moringa tree, another victim to the voracious appetite of an Acalolepta aesthetica, which has come to be known locally as the Queensland Longhorn Beetle (QLB). On that morning, HDOA entomologist Stacey Chun piled the logs in the corner of the insect containment unit and reluctantly added moringa to the growing list of tree species being attacked by QLB. Already, the insect had been confirmed in several kinds of trees, including citrus, kukui, breadfruit, and cacao. It was the cacao farmers who had first raised the alarm on QLB in 2018, when growers noticed healthy, producing trees suddenly devastated by a mysterious insect.

The case of A. aesthetica illustrates the difficulty of managing new invasive pests. Although it was first identified from a sample turned in to the HDOA office in 2009, no subsequent specimens were reported for several years. The Coordinating Group on Alien Pest Species (CGAPS), which provides tools and guidance for invasive species response in Hawaii, has estimated that one new insect species per day arrives at Hawaii’s ports. Most of the creatures that get here accidentally are individuals who will not survive in their new environment. Some will find their way and naturalize, but never rise to notice because they don’t cause much disruption to the world around them. But a handful will become pests that make headlines: coqui frogs, little fire ants, semi-slugs, two-lined spittlebugs. These are the introduced species that thrive in the Hawaiian environment, free from the predators and diseases that kept them in check in their home ranges, and able to exploit the environmental niches left open in an isolated island ecosystem.

Queensland Longhorn Beetle captured in Puna.

Moringa logs dropped off at HDOA in Hilo after the tree was attacked by QLB.

When a few more of the new longhorn beetles turned up in 2013, it was clear that the insect had found a way to survive and breed in Hawai‛i. It was not clear what this meant. An investigation into the insect’s background revealed little, only that it was from Queensland, Australia, and not known to be living anywhere else in the world – until it reached Hawai‛i. In Queensland, lush and verdant tropical forests surround landscapes of agricultural production, and never was this beetle reported as a pest. As just one of dozens of Cerambycid (longhorn) beetle species found in Queensland’s forests, this dull brown, cockroach lookalike didn’t particularly stand out. Very little was known about its life cycle or habits, or even which tree species it favored in its home range.

How it arrived in Hawai‛i was even more of a mystery. From genetic tests done by Dr. Sheina Sim at the USDA Agricultural Research Service in Hilo, it is clear that all of the QLB in Hawaii are descendants of the same line, meaning there had been only one introduction event. But due to the Jones Act, Hawaii receives very few commodities directly from other countries. Most goods crossing the Pacific must first head to the mainland to a designated international port, then be shipped back to Hawaii from there. No direct shipments from Queensland appeared to account for the insect arriving in Puna.

QLB larvae in dead logs. Photo courtesy S. Chun, HDOA.

QLB life stages (L-R): pupa, adult, and larva

Clues could be found in studying a closely related member of the QLB’s family, known as the Asian Longhorn Beetle (Anoplophora glabripennis), or ALB. Unlike its Queensland-based cousin, the ALB is a known problem-maker worldwide. In North America, where it was first spotted in 1996, costs of damage and control associated with ALB are now at nearly $1 billion. The ALB is so devastating that some European countries have taken the approach of killing every susceptible tree within a half-mile when a single insect is found.

The arrival of ALB in the 1990s coincided with the opening of direct trade between the US and mainland China, and the source of the introductions was deduced to be untreated wood packing materials that delivered hidden larvae along with their cargo. Because the behavior and life history of ALB appeared similar to Hawaii’s new and unwelcome guest, researchers hypothesized that it was possible QLB could have arrived here the same way. But was it possible the larvae could have survived a lengthy trip across the ocean and halfway back again?

A large hole in a moringa log where an adult QLB emerged. Photo: S. Chun, HDOA.

QLB have a brown, velvet-like appearance and have spines on their “neck”

The moringa logs in Stacey Chun’s HDOA lab offered up an answer to that question. Nearly eight months to the day after the logs were set aside, all but forgotten in the QLB insectary, a live adult emerged from the dried wood in April 2020. It had taken that larvae nearly eight months to develop to full adulthood (previously, Chun had recorded adult emergence as soon as 3 months). Eight months was more than enough time for a clutch of insect eggs to have traveled halfway around the world, unnoticed as they slowly developed inside of their wooden nest, to finally emerge as full-grown adults in an unsuspecting new home.

QLB and ALB are not the first of their kind to move into new territories via untreated wood, and unfortunately, they will likely not be the last. As humans enjoy the convenience and opportunity that new technology and increasing global traffic have afforded us, we must also contend with the downsides, one of which is the accidental movement of species into places where they have the potential to cause great harm. In the early aughts, in response to multiple infestations of new pests, the US and many other countries adopted a set of requirements that wood packaging material be certified as properly treated to kill pests. These rules were phases in and not fully implemented for several years, which is possibly the window during which QLB came into Hawaii. Subsequent research has also found that not all wood-boring insects are equally susceptible to the prescribed treatment methods and that the quality and efficacy of the packing wood treatment can vary between manufacturers, so even with enhanced regulations Untreated or inadequately treated wood remains a potential risk.

More information about the Queensland Longhorn Beetle can be found here.